Pre-print servers are a place to place share your academic work before actual peer review and subsequent publication. They are not so new completely new to academia, as many different disciplines have adopted pre-print servers to quickly share ideas and keep the academic discussion going. Many have praised the informal peer-review that you get when you post on pre-print servers, but I primarily like the speed.

But medicine is not one of those disciplines. Up until recently, the medical community had to use bioRxiv, a pre-print server for biology. Very unsatisfactory; as the fields are just too far apart, and the idiosyncrasies of the medical sciences bring some extra requirements. (e.g. ethical approval, trial registration, etc.). So here comes medRxiv, from the makers of bioRxiv with support of the BMJ. Let’s take a moment to listen to the people behind medRxiv to explain the concept themselves.

I love it. I am not sure whether it will be adopted by the community at the same space as some other disciplines have, but doing nothing will never be part of the way forward. Critical participation is the only way.

So, that’s what I did. I wanted to be part of this new thing and convinced with co-authors for using the pre-print concept. I focussed my efforts on the paper in which we describe the BeLOVe study. This is a big cohort we are currently setting up, and in a way, is therefore well-suited for pre-print servers. The pre-print servers allow us to describe without restrictions in word count, appendices or tables and graphs to describe what we want to the level of detail of our choice. The speediness is also welcome, as we want to inform the world on our effects while we are still in the pilot phase and are still able to tweak the design here or there. And that is actually what happened: after being online for a couple of days, our pre-print already sparked some ideas by others.

Now we have to see how much effort it took us, and how much benefit w drew from this extra effort. It would be great if all journals would permit pre-prints (not all do…) and if submitting to a journal would just be a “one click’ kind of effort after jumping through the hoops for the medRxiv.

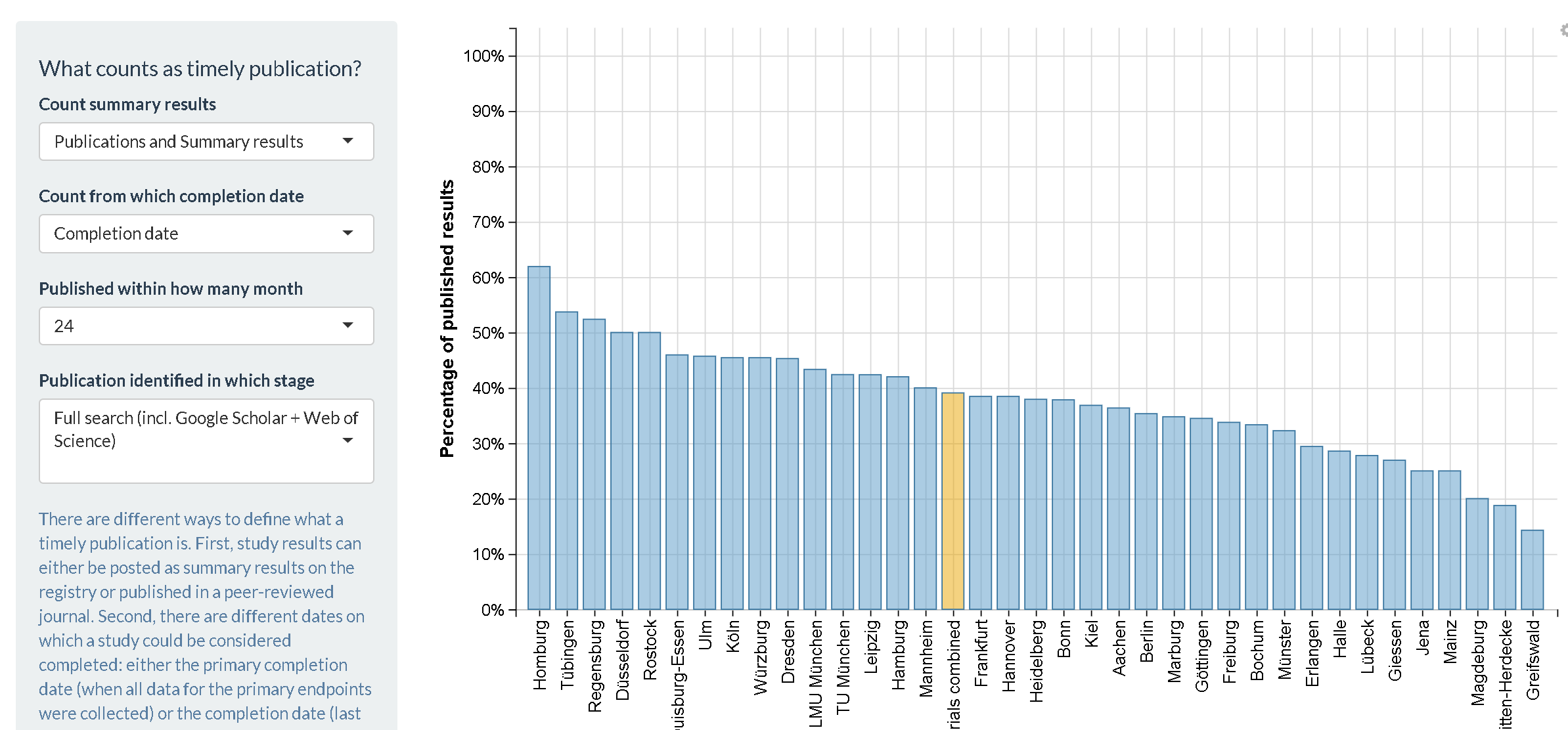

This is not my first pre-print. For example, the paper that I co-authored on the timely publication of trials from Germany was posted on biorXiv. But being the guy who actually uploads the manuscript is a whole different feeling.