Stroke patients can be severely affected by the clot or bleed in their brain. With the emphasis on “can”, because the clinical picture of stroke is varied. The care for stroke cases is often organized in stroke units, specialized wards with the required knowledge and expertise. I forgot who it was – and I have not looked for any literature to back this up – but a MD colleague told me once that stroke units are the best “treatment” for stroke patients.

Why am I telling you this? Because the next paper I want to share with you is not about mild or moderately affected patients, nor is it about the stroke unit. It is about stroke patients who end up at the intensive care unit. Only 1 in 50 to 100 of ICU patients are actually suffering from stroke, so it is clear that these patients do not make up the bulk of the patient population. So, all the more reason to bring some data together and get a better grip on what actually happens with these patients.

That is what we did in the paper “Long-Term Mortality Among ICU Patients With Stroke Compared With Other Critically Ill Patients”. The key element of the paper is the sheer volume of data that were available to study this group: 370,386 ICU patients, of which 7,046 (1.9%) stroke patients (of which almost 40% with intracerebral hemorrhage, a number far higher than natural occurrence).

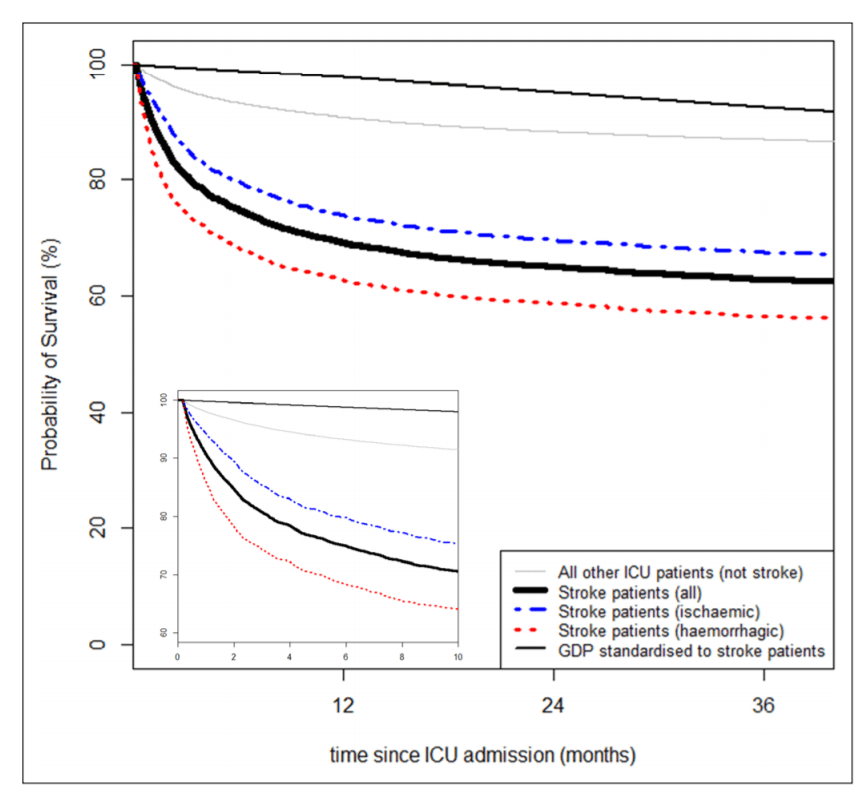

The results are basically best summed up in the Kaplan Meier found below – it shows that in the short run, the risk of death is quite high (this is after all an ICU population), but also that there is a substantial difference between ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Hidden in the appendix are similar graphs where we plot also different diseases (e.g. traumatic brain injury, sepsis, cardiac surgery) that are more prevalent in the ICU to provide MDs with a better feel for the data. Next to these KM’s we also model the data to adjust for case-mix, but I will keep those results for those who are interested and actually read the paper.

Our results are perhaps not the most world shocking, but it is helpful for the people working in the ICU’s, because they get some more information about the patients that they don’t see that often. This type of research is only possible if there is somebody collecting this type of data in a standardized way – and that is where NICE came in. “National Intensive Care Evaluation” is a Dutch NGO that actually does this. Nowadays, most people know this group from the news when they give/gave updates on the number of COVID-19 patients in the ICU in the Netherlands. This is only possible because there was this infrastructure already in place.

MKV took the lead in this paper, which was published in the journal Critical Care Medicine with DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004492.

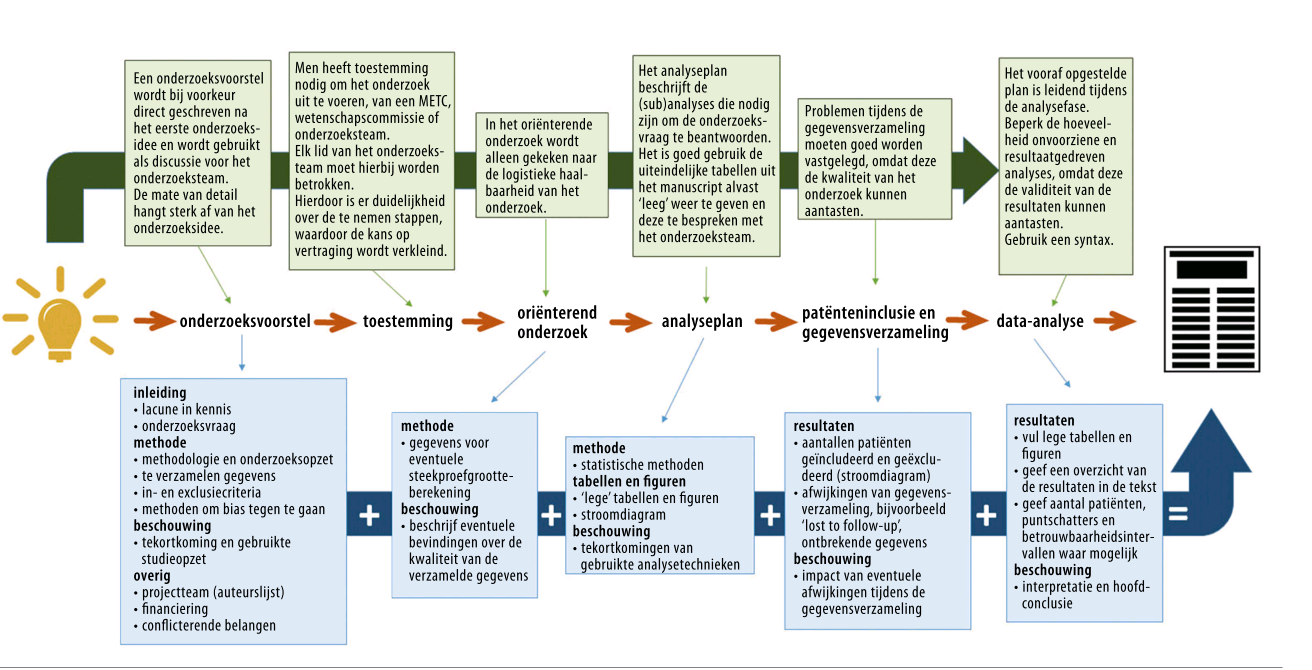

This is a special paper to me, as this is a paper that is 100% the product of my team at the CSB.Well, 100%? Not really. This is the first paper from a series of projects where we work with open data, i.e. data collected by others who subsequently shared it. A lot of people talk about open data, and how all the data created should be made available to other researchers, but not a lot of people talk about using that kind of data. For that reason we have picked a couple of data resources to see how easy it is to work with data that is initially not collected by ourselves.

This is a special paper to me, as this is a paper that is 100% the product of my team at the CSB.Well, 100%? Not really. This is the first paper from a series of projects where we work with open data, i.e. data collected by others who subsequently shared it. A lot of people talk about open data, and how all the data created should be made available to other researchers, but not a lot of people talk about using that kind of data. For that reason we have picked a couple of data resources to see how easy it is to work with data that is initially not collected by ourselves.

Easter brought another publication, this time with the title

Easter brought another publication, this time with the title

Together with HdH and AvHV I wrote an article for the Dutch NTVG on Mendelian Randomisation in the Methodology series, which was published online today. This is not the first time; I wrote in the NTVG before for this up-to-date series (not

Together with HdH and AvHV I wrote an article for the Dutch NTVG on Mendelian Randomisation in the Methodology series, which was published online today. This is not the first time; I wrote in the NTVG before for this up-to-date series (not

At the department of Clinical Epidemiology of the LUMC we have a continuous course/journal in which we read epi-literature and books in a nice little group. The group, called Capita Selecta, has a nice website which can be

At the department of Clinical Epidemiology of the LUMC we have a continuous course/journal in which we read epi-literature and books in a nice little group. The group, called Capita Selecta, has a nice website which can be

Today, an educational article on crossover studies, written by TNB and JGvdB and myself is published in the

Today, an educational article on crossover studies, written by TNB and JGvdB and myself is published in the