I wrote a blog post for BMC, the publisher of Thrombosis Journal in order to celebrate blood clot awareness month. I took my two favorite subjects, i.e. stroke and coagulation, and I added some history and voila! The BMC version can be found here.

When I look out of my window from my office at the Charité hospital in the middle of Berlin, I see the old pathology building in which Rudolph Virchow used to work. The building is just as monumental as the legacy of this famous pathologist who gave us what is now known as Virchow’s triad for thrombotic diseases.

In ‘Thrombose und Embolie’, published in 1865, he postulated that the consequences of thrombotic disease can be attributed one of three categories: phenomena of interrupted blood flow, phenomena associated with irritation of the vessel wall and its vicinity and phenomena of blood coagulation. This concept has now been modified to describe the causes of thrombosis and has since been a guiding principle for many thrombosis researchers.

The traditional split in interest between arterial thrombosis researchers, who focus primarily on the vessel wall, and venous thrombosis researchers, who focus more on hypercoagulation, might not be justified. Take ischemic stroke for example. Lesions of the vascular wall are definitely a cause of stroke, but perhaps only in the subset of patient who experience a so called large vessel ischemic stroke. It is also well established that a disturbance of blood flow in atrial fibrillation can cause cardioembolic stroke.

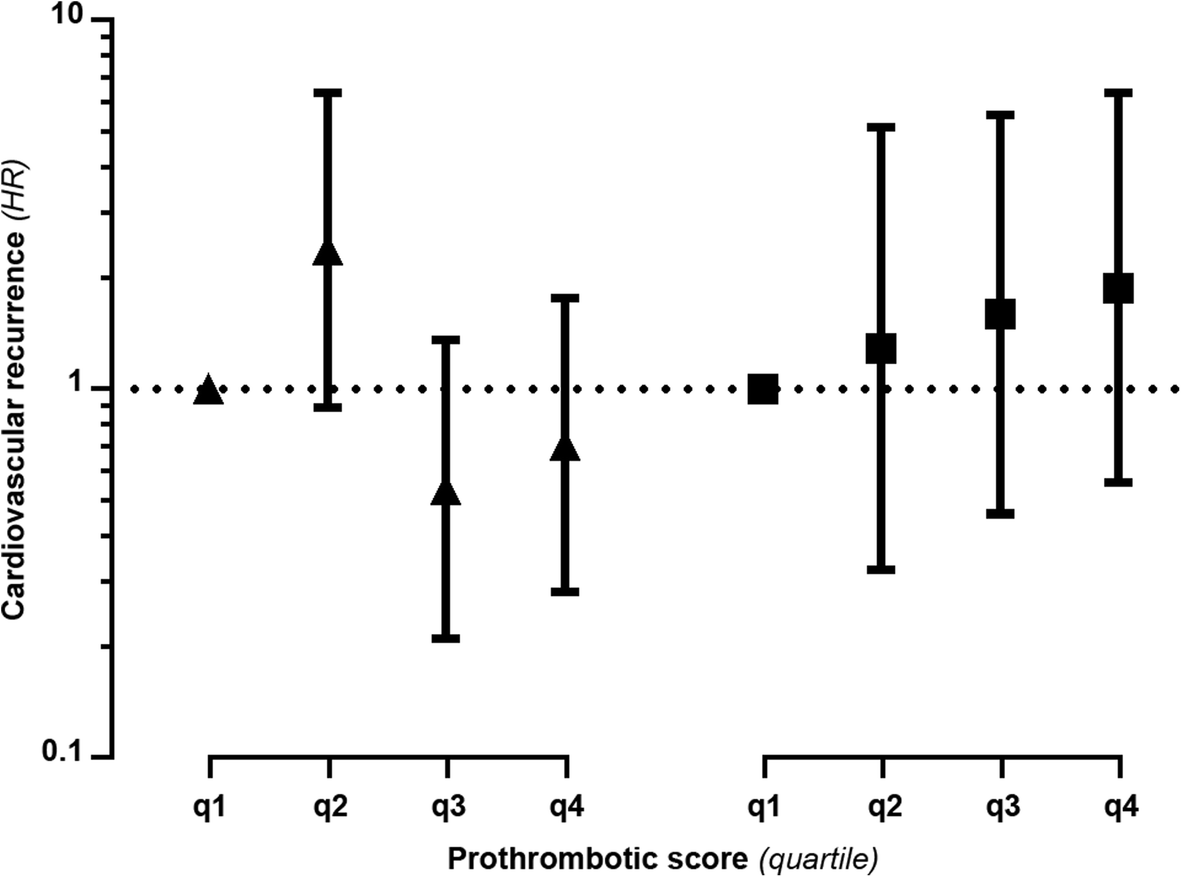

Less well studied, but perhaps not less relevant, is the role of hypercoagulation as a cause of ischemic stroke. It seems that an increased clotting propensity is associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke, especially in the young in which a third of main causes of the stroke goes undetermined. Perhaps hypercoagulability plays a much more prominent role then we traditionally assume?

But this ‘one case, one cause’ approach takes Virchow’s efforts to classify thrombosis a bit too strictly. Many diseases can be called multi-causal, which means that no single risk factor in itself is sufficient and only a combination of risk factors working in concert cause the disease. This is certainly true for stroke, and translates to the idea that each different stroke subtype might be the result of a different combination of risk factors.

If we combine Virchow’s work with the idea of multi-causality, and the heterogeneity of stroke subtypes, we can reimagine a new version of Virchow’s Triad (figure 1). In this version, the patient groups or even individuals are scored according to the relative contribution of the three classical categories.

From this figure, one can see that some subtypes of ischemic stroke might be more like some forms of venous thrombosis than other forms of stroke, a concept that could bring new ideas for research and perhaps has consequences for stroke treatment and care.

Figure 1. An example of a gradual classification of ischemic stroke and venous thrombosis according to the three elements of Virchow’s triad.

However, recent developments in the field of stroke treatment and care have been focused on the acute treatment of ischemic stroke. Stroke ambulances that can discriminate between hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke -information needed to start thrombolysis in the ambulance-drive the streets of Cleveland, Gothenburg, Edmonton and Berlin. Other major developments are in the field of mechanical thrombectomy, with wonderful results from many studies such as the Dutch MR CLEAN study. Even though these two new approaches save lives and prevent disability in many, they are ‘too late’ in the sense that they are reactive and do not prevent clot formation.

Therefore, in this blood clot awareness month, I hope that stroke and thrombosis researchers join forces and further develop our understanding of the causes of ischemic stroke so that we can Stop The Clot!

![2018-11-08 12_43_09-RATIO instol zymogen.ppt [Compatibility Mode] - PowerPoint](https://bobsiegerink.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/2018-11-08-12_43_09-ratio-instol-zymogen-ppt-compatibility-mode-powerpoint-e1541681262735.png)

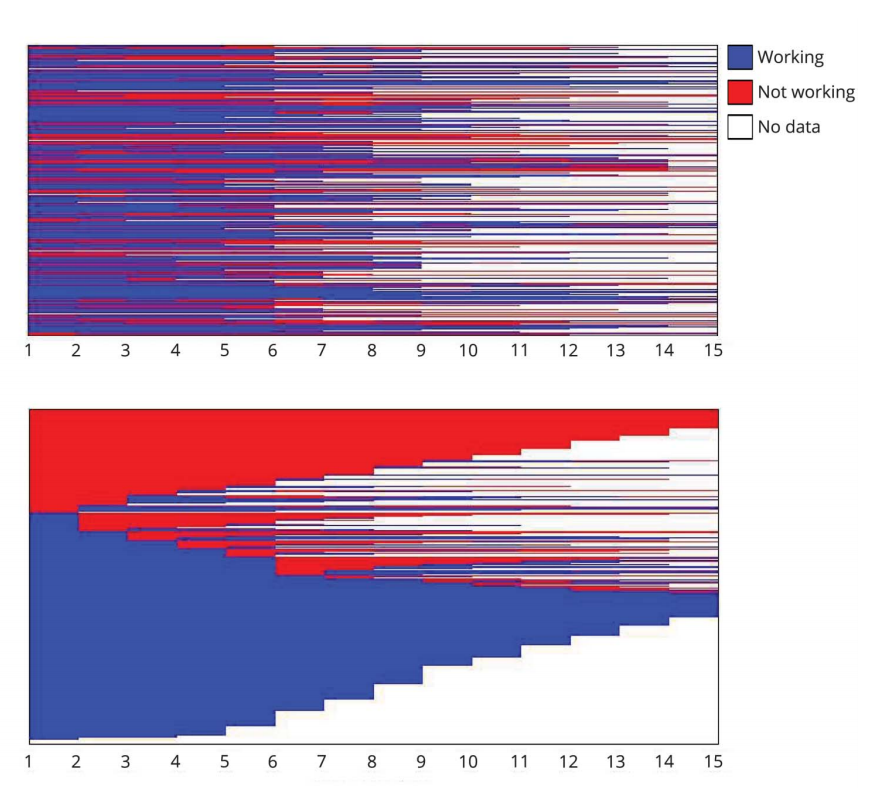

This is a special paper to me, as this is a paper that is 100% the product of my team at the CSB.Well, 100%? Not really. This is the first paper from a series of projects where we work with open data, i.e. data collected by others who subsequently shared it. A lot of people talk about open data, and how all the data created should be made available to other researchers, but not a lot of people talk about using that kind of data. For that reason we have picked a couple of data resources to see how easy it is to work with data that is initially not collected by ourselves.

This is a special paper to me, as this is a paper that is 100% the product of my team at the CSB.Well, 100%? Not really. This is the first paper from a series of projects where we work with open data, i.e. data collected by others who subsequently shared it. A lot of people talk about open data, and how all the data created should be made available to other researchers, but not a lot of people talk about using that kind of data. For that reason we have picked a couple of data resources to see how easy it is to work with data that is initially not collected by ourselves. “Navigating numbers” is a series of Masterclass initiated by a team of Charité researchers who think that our students should be able to get more familiar how numbers shape the field of medicine, i.e. both medical practice and medical research. And I get to organize the next in line.

“Navigating numbers” is a series of Masterclass initiated by a team of Charité researchers who think that our students should be able to get more familiar how numbers shape the field of medicine, i.e. both medical practice and medical research. And I get to organize the next in line.

I am very happy and honored that i can tell you that our paper “

I am very happy and honored that i can tell you that our paper “![logo-home[1]](https://bobsiegerink.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/logo-home1.png)